Maintaining Control within Incident Response Investigations - Part 2

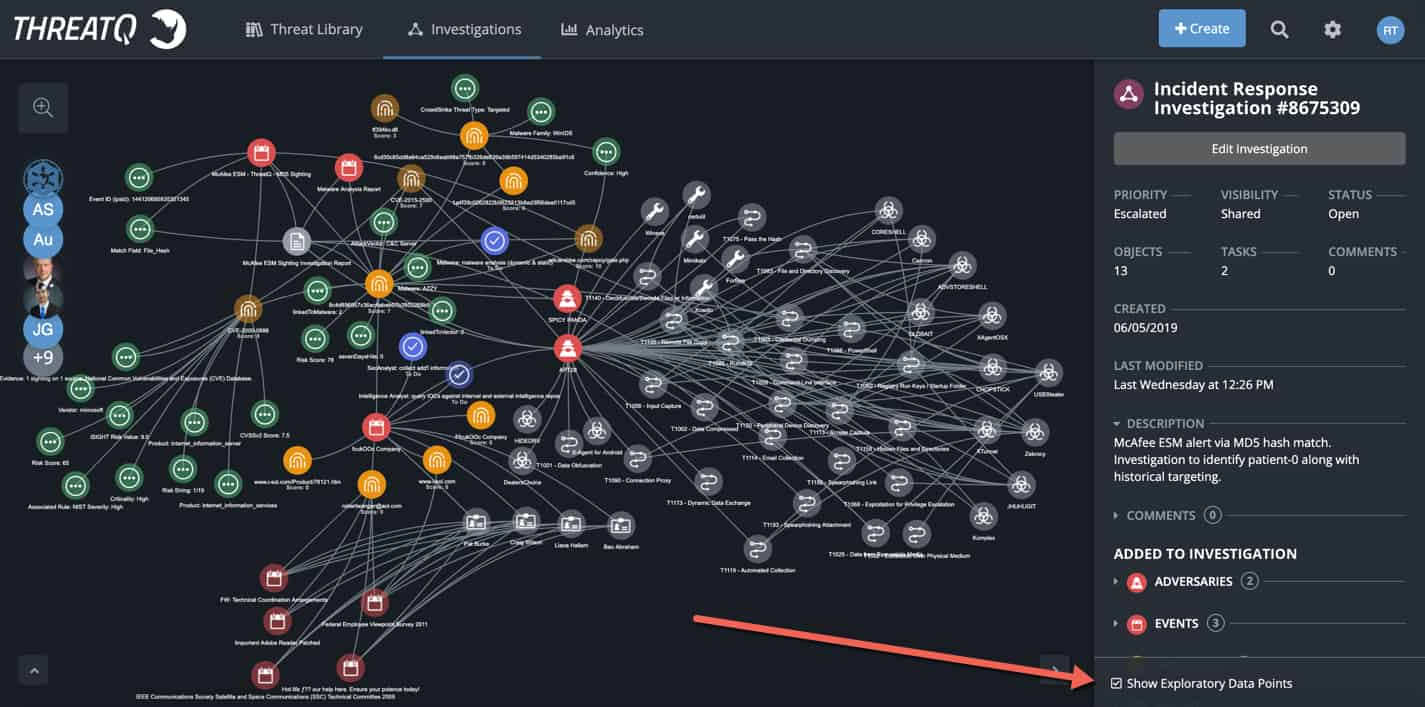

POSTED BY RYAN TROSTIn Part 1 of this series I landed on a recalibrated definition of incident pruning that addresses the nuances of incident deadheading and incident pruning. Now, I want to demonstrate how ThreatQ Investigations can handle both incident thinning and incident deadheading methodologies. ThreatQ Investigations has two features specifically designed to support both incident pruning approaches, including individual vs. shared investigation visibility and exploratory data points.

Incident Deadheading – Private vs. Shared Investigations

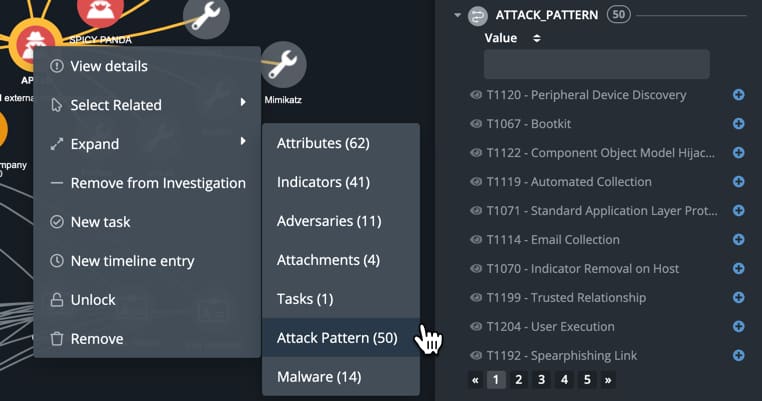

Investigations (or incidents) can be private or shared. Private investigations are not visible to other ThreatQ contributors, whereas shared investigations are accessible by any person with a ThreatQ account. Each analyst viewing an investigation has an independent view of the investigation which allows the capability to explore endless investigation paths without interfering with other analysts’ views of the investigation. This is key to incident pruning because an incident response team lead (or incident authority) can delegate components of an investigation to individuals or smaller teams and as tasks are accomplished those results can be published to the global investigation. This is a cornerstone aspect of ThreatQ Investigations because it allows the investigation lead to dictate a validation workflow or process before posting content to the larger team. This also helps ensure analysts are focused on their task at hand and not constantly distracted by other analysts’ research paths.

This capability supports incident deadheading because the incident response team lead can remove nodes from the incident, either when tasks return negative findings or when the investigation follows a different path and the node is no longer viable. This ensures complex investigations remain digestible by the team and focus is maintained on higher fidelity efforts and thought processes.

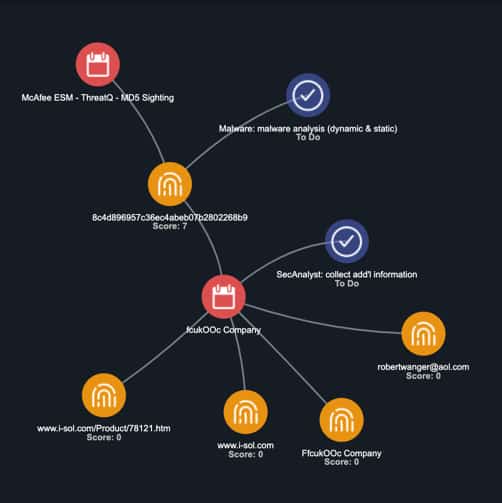

When an object is globally viewable in the investigation the object has a ‘solid fill color’ (e.g., McAfee ESM – ThreatQ – MD5 Sighting). When the object is still isolated to a specific investigation it has a ‘translucent fill color’ (e.g., McAfee ESM Sighting Investigation Report, Event ID, Match Field, etc.) as demonstrated below in Figure 1. To publish an investigation path to the larger group an analyst must right click and select “Add to Investigation” which will propagate to all views of the investigation.

Figure 1

Incident Thinning – Exploratory Data Points

Incident thinning is the ability to declutter an investigation and return to a pre-approved state, similar to reverting back to a previous host snapshot. When “show exploratory data points” is checked it allows the team to document investigation paths in all directions as they think outside the box and selectively add only the relevant paths to the global [shared] investigation.

Figure 2

After the team enumerates through the options and pinpoints the correct path, they can unselect “show exploratory data points” and pivot back to only the core relevant pieces of the investigation. This is extremely beneficial when dealing with high volume datasets (i.e., MITRE ATT&CK™ having 155+ possible techniques, an abundance of indicators (direct and indirect), fast flux DNS, adversary aliases, potentially numerous malicious emails and/or victims, etc.)

Figure 3

Use Case – The Initial Steps of an Incident

In this use case, an incident response investigation is triggered from a SIEM alert. The premise of this use case isn’t to provide step-by-step incident response instructions nor provide never before seen indicators, adversaries or tactics, but rather highlight several key features within ThreatQ Investigations that allow an IR team lead to properly prune an incident based on threat prioritization and resource responsibility. The investigation does contain several characteristics that will require incident pruning – both deleting and de-prioritization.

To set the stage, the investigation will be escalated to an incident which will extend visibility to fellow security operations center (SOC) teams encompassing security analyst, incident response, malware analysis, threat intelligence and vulnerability assessment teams.

Each team is responsible for a specific component of the investigation. As information is collected and validated it is “added” to the bigger investigation. As with any security team dichotomy/taxonomy, responsibility bleedover across tasks varies organization to organization depending on skill set, time, etc. The role/task delineation in this use case is just one example, but the IR investigation premise will remain the same across organizations. Also note there are numerous ways to approach an investigation so the sequence of events may also differ depending on the organization and situation.

Step #1: Security Analysts triage the SIEM alert

The security analyst will triage the alert to create an investigation [Figure 4] within ThreatQ Investigations containing the SIEM alert and any immediate information gleaned from the alert. At this point, the investigation is just beginning and this visualization serves as the incident foundation.

It quickly surfaces that the alert was triggered by a spear phish attempt via a malicious attachment. The email in question is tracked down and added to the investigation which includes the MD5 hash, email subject and email sender.

Figure 4

Step #2: Malware analyst performs analysis on MD5 hash

The malware analyst submits the corresponding MD5 hash file to an internal sandbox. Having successfully detonated the specimen, the malware analyst publishes the malware report and the command and control FQDN and URL to the larger global investigation [Figure 5]. The analyst also queries the hash in external malware repositories (i.e., VirusTotal) to glean any additional information or community commentary. Note: Most teams are very cautious NOT to use VirusTotal as the sandbox itself because submitted malware samples are published to the general public which likely includes the attackers who are monitoring VirusTotal for their malware.

Figure 5

Step #3: Query internal and external intelligence repositories

Since the email and malware analysis surfaced several indicators of compromise (IOCs) the security analyst and/or intelligence analyst queries the IOCs against internal and external intelligence repositories to gain any additional insights to assist with the investigation. Internal repositories include the ticketing system, historical SIEM alerts and threat intelligence platforms. External intelligence repositories include the commercial intelligence providers (i.e., FireEye Intelligence, CrowdStrike, Flashpoint, Digital Shadows, Intel-471, RecordedFuture, etc.) or third-party query services (i.e., PassiveTotal, DomainTools, FarSight Security, etc.).

The queries identify three external intelligence repositories that provide some helpful information. Some information is a bit too detailed to publish to the global investigation, but provides good situational awareness for certain teams. For example, one of the commercial providers attributes the hash to an adversary, APT28 (aka Spicy Panda) so that creates a new path for validation and exploration [always trust but verify] for the intelligence team.

Up until this point, the investigation has been limited to one security analyst, one incident response lead and one malware analyst, each with a specific role and a small handful of IOCs within the investigation. As such, the investigation has not warranted incident pruning using either methodology. But as more information is gathered and the intelligence and vulnerability team get involved, the need for incident pruning is inevitable.

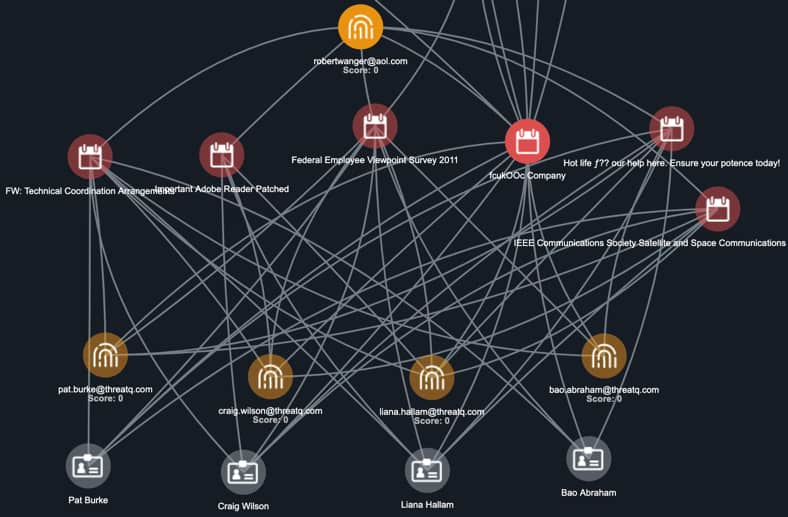

Step #4: Threat intelligence analyst digs into email sender

The intelligence analyst focuses on gathering additional intelligence on the attacker’s email address (robertwanger [at] aol [dot] com). Typically burner addresses don’t yield highly actionable results, but sometimes it does help to identify previous attacks or registered domains which might help with existing incident response efforts.

In this situation, chasing the attacker’s email address identified four previous attacks. This initiates a deeper dive into attack vector patternization and targeting insights.

Step #5: Threat intelligence analyst performs victimology

By discovering the previous email attacks, the intelligence analyst can begin to perform some quick victimology analysis to try to determine “why” those individuals were targeted. Did the attacker focus on soft targets to increase their likelihood of success before turning their attention to the hard targets – the end goal? Or did they directly attack their final targets?

Including previous spearphish attacks and respective targets within the global investigation is valuable, but pulling in all associated information for those attacks can quickly consume the link analysis graphic. This is why it is so critical to selectively publish information to the global investigation. The intelligence analysts will want to keep it visible within their view but the IR team lead might not publish it to the global view [Figure 6].

Figure 6

This is the first incident pruning effort, specifically incident thinning, where the information exceeds what is desirable to include in the global investigation. The initial information is helpful for the intelligence team but not relevant enough (at this point) to publish to the larger team. If additional information about one of the previous attacks or targets is discovered that will help the current investigation, then the pertinent subset of information should be published to the global team.

Step #6: Threat intelligence analyst confirmed adversary attribution

In step #3, two premium intelligence providers have associated an adversary group, APT28 and SpicyPanda, to the hash value. Though this intelligence is slightly more trustworthy given the source is a paid intelligence feed, every piece of external intelligence should be validated to some degree. The intelligence team works to verify the information, comparing the externally provided adversary profile information to the internal investigation information to identify similarities.

This step includes incident pruning in either form depending on whether the attribution was already added to the investigation for global visibility. If the adversary attribution was included in the investigation and the team cannot verify its accuracy, the team can remove [deadhead] it from the investigation. However, if the intelligence team did not include it in the global investigation already, then incident thinning will de-prioritize that piece of intelligence and it will not be broadcast to the larger investigation team.

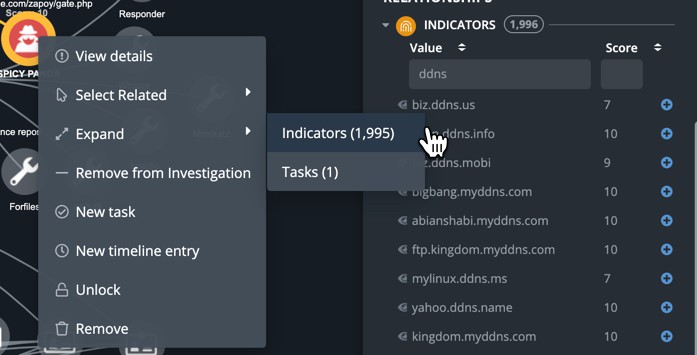

Step #7: Incident Response analyst performs ‘rear-view mirror search’

In an effort to cast an “APT28 indicator-centric” net to try and identify either a pattern of activity or potentially try to identify any internally initiated egress communication to APT28’s malicious infrastructure, the intelligence analyst displays all the indicators associated with the adversary and runs the respective operation. Since throughout the lifecycle of the adversary ~1,995 indicators are associated to the adversary group, incident pruning efforts are required to maintain focus [Figure 7].

If the analyst displays all those indicators, the graphic will quickly become unusable. Instead, the analyst can filter through the list and include the indicators more relevant to the investigation, whether designated by doppleganger syntax, threat score, or chronologically, by clicking on the ‘eye-ball’ immediately before the IOC to review the IOC’s summary.

Including the relevant indicators in the local investigation allows for the ability to trigger an Operation to query them against internal logs. If a fruitful result occurs it can be published to the global investigation for larger visibility. This is an example of incident thinning — selectively determining which objects/nodes to publish globally and which ones have false negative results, and therefore, are not relevant to the investigation and are not published globally.

Figure 7

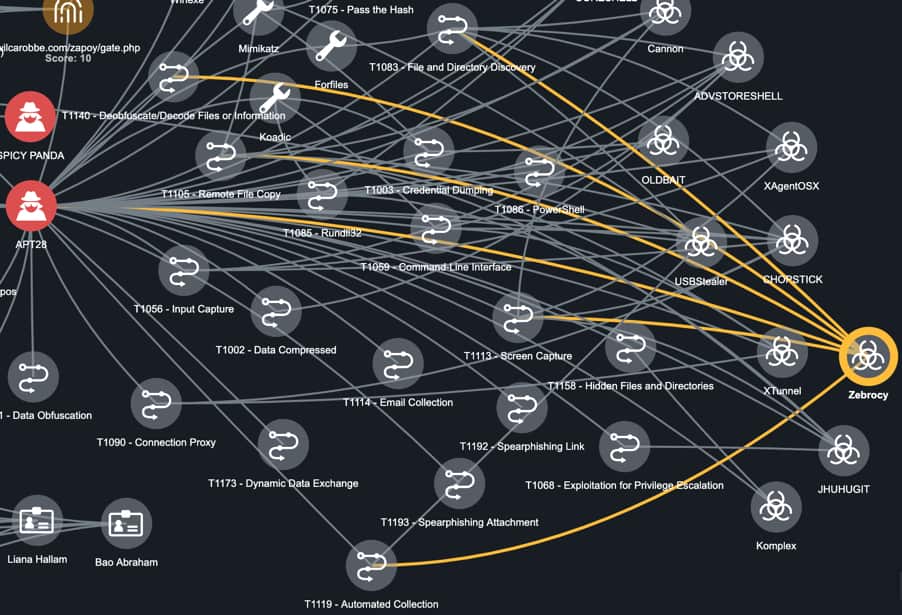

Step #8: Threat intelligence analyst and Incident Response analyst map adversary to MITRE ATT&CK (software, tool, TTP) to help uncover possible investigation paths

Although adversary attribution itself is not immediately actionable per se, it does help the team focus on the respective TTPs to ensure a unified defense. This step is a joint action between the intelligence analysts and incident response team to help prioritize investigation paths. In this situation [Figure 8], APT28 has the following characteristics associated to them via MITRE ATT&CK:

- 50 TTPs [attack patterns]

- 14 malware software

- 6 malicious tools

Figure 8

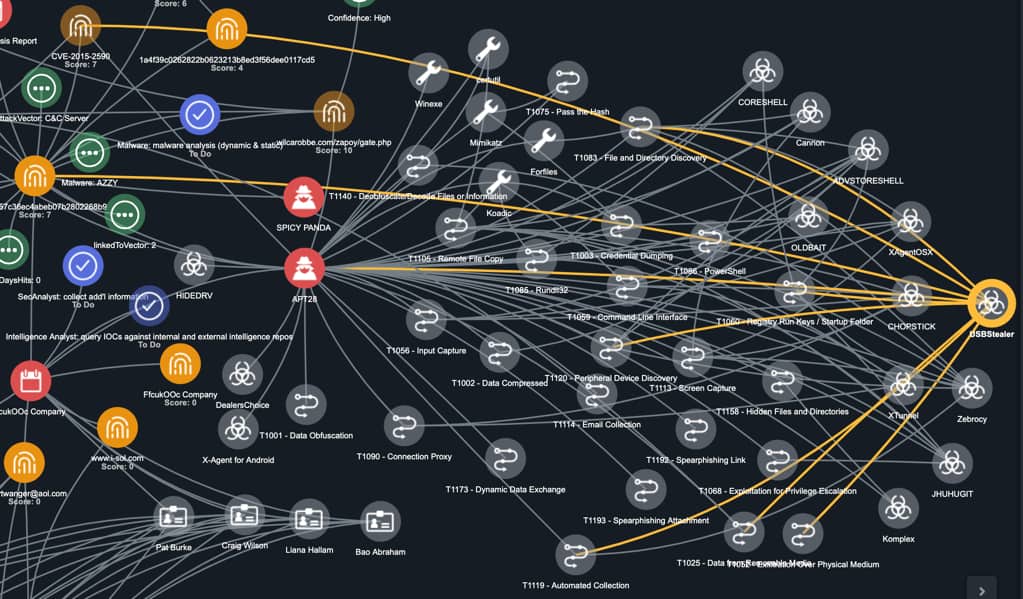

Fifty additional objects on the link analysis graph is busy but do-able; especially if only for an individual or team view versus publishing it to the global investigation for the whole team. But in which direction should the team allocate manpower? Once all three categories [TTPs, software, tools] are added to the investigation and a cursory review eliminates some of the “noise,” it creates a smaller, prioritized list of investigation tasks. This is where the “gut feeling” of the intelligence team and IR team comes into play. If the adversary has gravitated to a certain style recently, that will be prioritized at the top. Otherwise, a “paper weight” litmus test can be used to try to identify which combination of TTPs, malware and tools have connecting edges. In a paper weight test, the analysts evaluate each node across the three categories to determine which nodes have the most correlations (e.g., connecting edges). This approach is not scientific but indirectly speaks to the nature of probabilities.

For instance, using the methodology to compare edges of Zebrocy and USBStealer finds that Zebrocy has six edge associations [Figure 9]:

- 1 association to APT28

- 5 associations to APT28’s Attack Patterns

Figure 9

However, selecting USBStealer reveals nine edge associations [Figure 10]:

- 1 association to APT28

- 1 association to MD5 hash (from SIEM alert)

- 1 association to SHA-256 hash

- 1 association to CVE-2015-2590

- 5 associations to APT28’s Attack Pattern

Figure 10

The linkage to the hash values immediately prompts the team to focus on USBStealer as the malware software used in the attack. This creates a highly probable investigation path for the team to chase. At this point, the intelligence analyst and incident response team agree on the effort and globally publish the information to the investigation which immediately propagates to other analysts working on the investigation — primarily the malware team for verification.

Although it is still very early in the investigation of a relatively simple and straightforward spearphish investigation, analysts already have relied heavily on incident pruning, demonstrating that even simple investigations can gain complexity quickly. That complexity is not purely based on the attack itself, but also the supplemental metadata each investigation requires to ensure every stone has been uncovered. Incident pruning is a critical process for every IR team, whether through incident thinning to leverage the individual view of the investigation and only publish the most relevant information to the larger global investigation view, or through incident deadheading where the team removes false negatives or irrelevant information from the investigation in order to maintain a narrower investigation scope.

I hope this use case brought to light how to apply ThreatQ Investigations to incident pruning. In the third and final part of the series, I’ll address some frequently asked questions about incident pruning.

0 Comments