WannaCry from the Bleachers…

POSTED BY NEAL HUMPHREYOr Wanna Cry or Wanna Crypt or Wcry2 or EternalBlue with Doublepulsar, you get the idea.

Update: While working on this Blog Post we have seen 2 new ransomware campaigns (Nyetya and Peytra). The amount of data so far produced for these new ransomware versions is smaller than the initial drop of information for WannaCry. That being said, the collection, organization and protection scenarios are the same.

As an employee of a company dedicated to cybersecurity, and especially threat intelligence, I watched the unfolding of the WannaCry infection with a bit more than a passing interest. I was following the feed info from several lists, and talking to old friends and current partners about what they were seeing and how things were or were not changing.

ThreatQuotient is an interesting company, and frankly a little different from other vendors that are in the space, by design. We don’t have a threat intel team. We don’t aggregate external data and then resell it, nor do we gather intel and add more to it through enrichment and sell it. We allow our customers to bring in what they wish, when and how they wish.

This differentiation allows us to point out interesting things that happen without any conflict of interest.

So what was interesting in WannaCry, besides the use of a combination of two exploits from the equation group dump?

One notable aspect is the sheer amount of information that was collected and published to the internet in such a short period of time. From the initial posts that started on May 12 through the avalanche of blogs, publications, white papers etc. that hit on the 15 and has continued almost daily (and as a case in point you can add this blog to the list).

To give a little perspective to the numbers, let’s go to Google Trends:

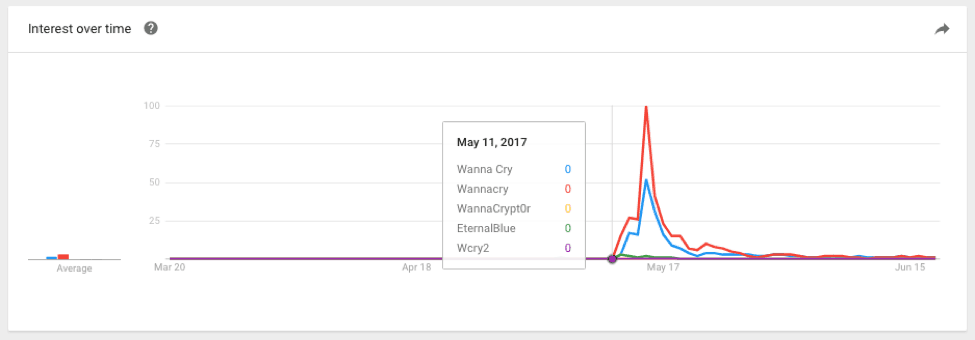

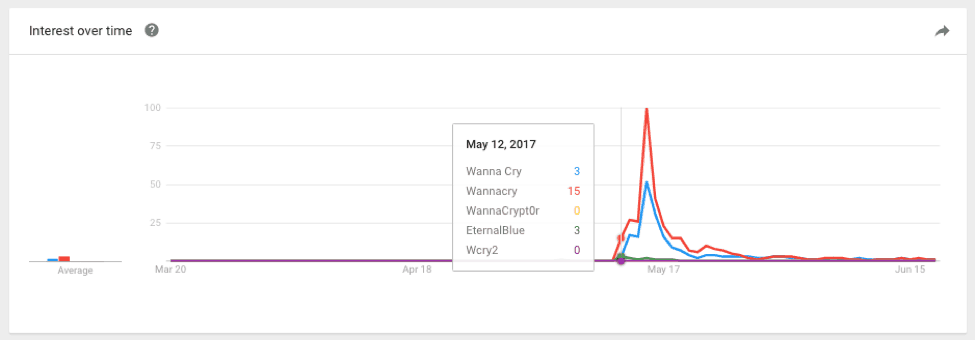

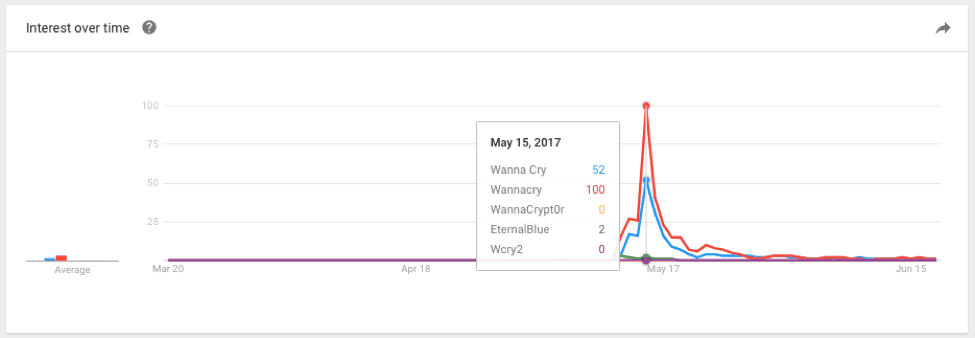

Below are a series of Interest Over Time graphs using a variety of terms for WannaCry. Google Trends measures the terms based on “Interest over Time” which is defined as:

Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. Likewise a score of 0 means the term was less than 1% as popular as the peak.

With that in mind, take a look at the results below.

Figure 1: May 11

Figure 2: May 12

Figure 3: May 15

Why is this trend important? It shows us that as a term, WannaCry didn’t exist on the wider internet until May 12. Once the ransomware was found and named on the 12th we see the term rise in popularity quickly, peaking on the 15th. This is well after the “off” switch or domain was found and registered on the 12th.

What’s significant is that indicators, malware forensic information and samples were generally available on the 12th but this data was quickly overwhelmed by the sheer amount of publications that ensued.

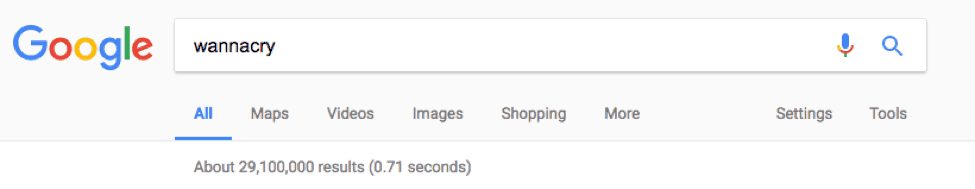

I did A LOT of web searching for publications of WannaCry details, but let’s just make it simple:

Figure 4: Search run June 29 – 12:23pm ET

That’s 29 million hits. Let that sink in: 29 MILLION results.

We can do some google foo to pick out specific sources, types or responses, etc., but however you slice it, the IT industry has spun out a ton of information in very short order. How can an organization quickly determine what part of this information applies to their environment and how to use it to best defend their specific network against these attacks?

As an agnostic threat intelligence platform, ThreatQ is uniquely suited to help answer that question.

Let’s run the collection, organization and protection capabilities of ThreatQ using the following sources for indicator collection:

Multiple Blog Posts – Sophos, Proofpoint, Cisco Talos, McAfee, KrebsonSecurity.

I used a series of ingestion capabilities. For example, I directly uploaded the USCert and X-Force exchange STIX documents, used some simple copy/paste and parse unstructured data from the blog posts, and employed the AlienVault OTX Pulse API.

I quickly had a large collection of indicators that only kept growing as more hash-based indicators were identified and published. Not surprisingly the Tor nodes, IP addresses and domains stayed relatively stable.

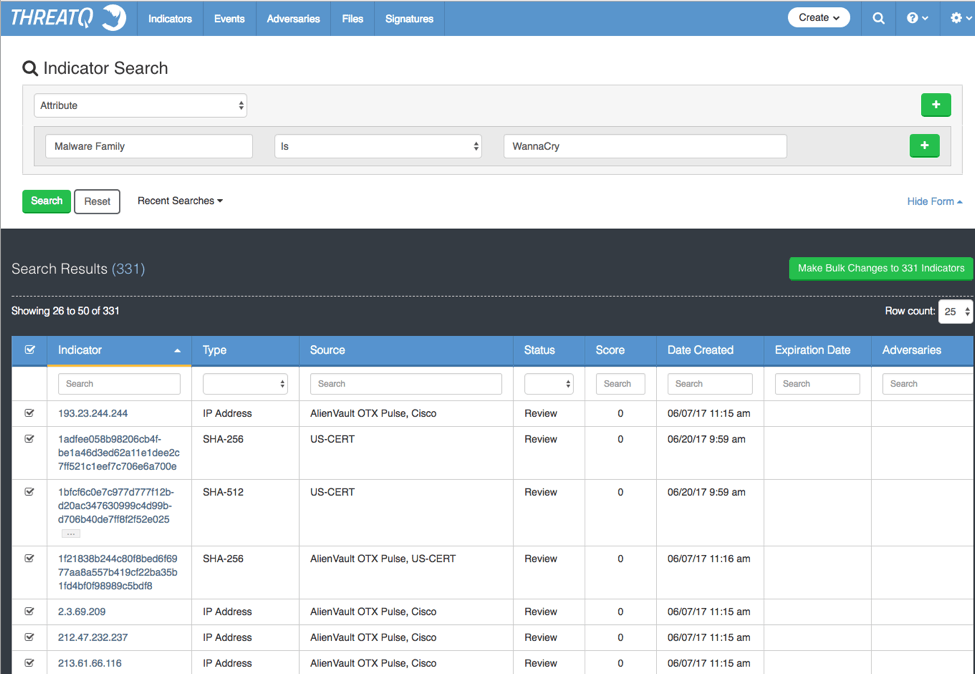

Figure 5: – ThreatQ Advanced Search using simple Attribute Key of Malware Family and a value of WannaCry (picture from the ThreatQ threat intelligence platform version 3.1.1)

After some more collecting I ended up with a total of 802 indicators identified, 502 hashes of SHA1, SHA256 and SHA512, leaving us with around 300 indicators of the FQDN, IP, URL, and Email types.

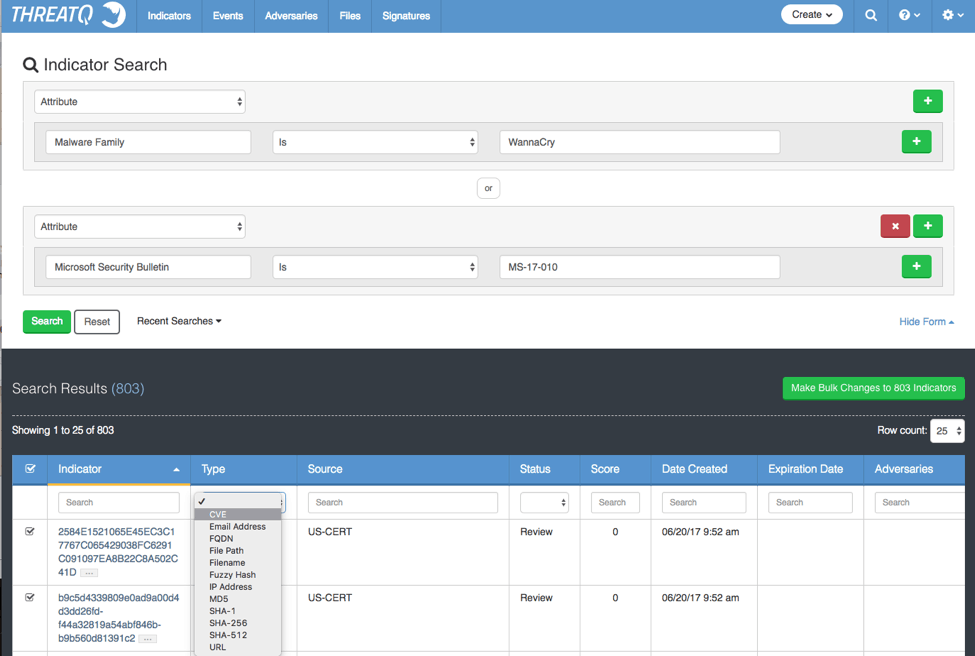

Figure 6: – Adding secondary attribute key of Microsoft Security Bulletin and value of MS-17-2010 (picture from ThreatQ version 3.1.1)

The screenshot above reveals something particularly interesting. Not only did I collect observables/indicators, I was also able to collect and identify the CVEs that EternalBlue took advantage of so I was able to collect and link the Microsoft security bulletin along with all the relevant information they provided at that time.

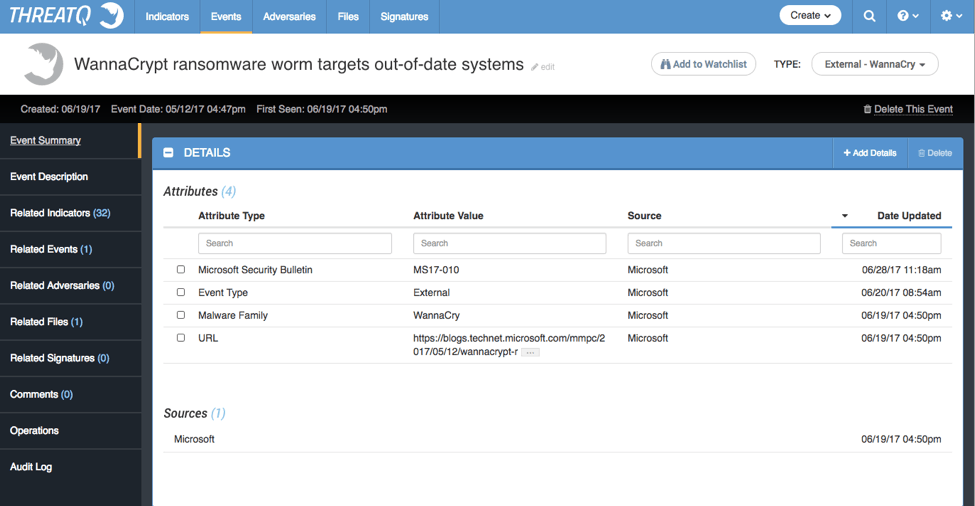

Figure 7: – Analyst created External Event within the ThreatQ threat intelligence platform. Sourced from Microsoft specific to the release of Microsoft Security Bulletin: MS17-010 (picture from ThreatQ version 3.1.1)

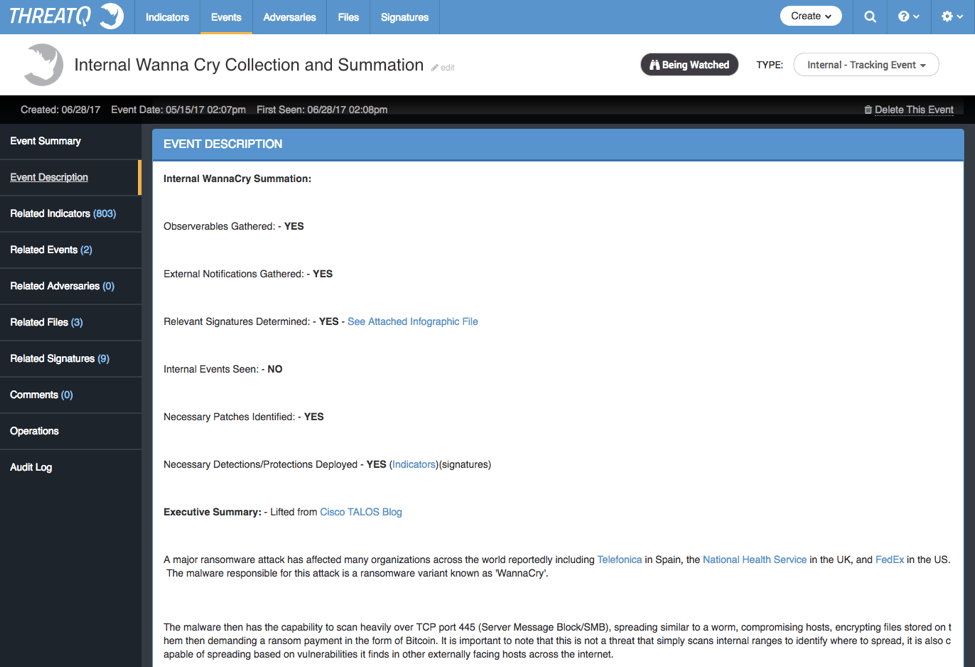

Now with multiple events collected that contain indicators, CVEs and even Snort signatures, I created an internal event that allows for direct tracking and distribution of information to anyone that needs it, internally or external to the company.

Figure 8: – Analyst created Adversary Profile for Wanna Cry (picture from ThreatQ version 3.1.1)

Via ThreatQ integrations I can not only provide the summary to executives, I can track internal vs external events automatically via bi-directional interactions with SIEMs and verify any known issues deeper in the network via Vuln scan data referencing a CVE lookup:

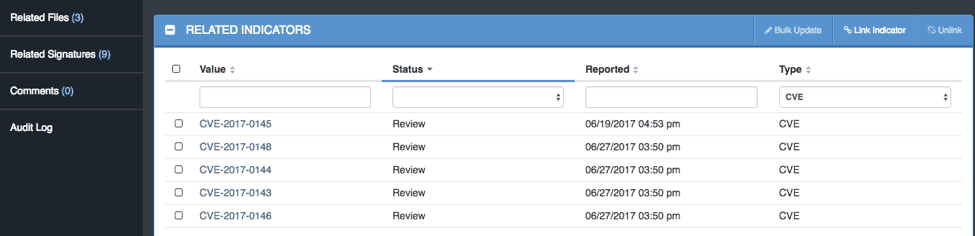

Figure 9 – Related Indicators, CVE’s in this case, from the Analyst created Adversary Profile for Wanna Cry (picture from ThreatQ version 3.1.1)

I can also take an active stance by marking indicators for export to detection systems, such as endpoint detection based on openIOC signatures, SHA256 or MD5 indicators in a blacklist, along with sending IPs, Domains or URLs to NGIPS or NGFW dynamic lists.

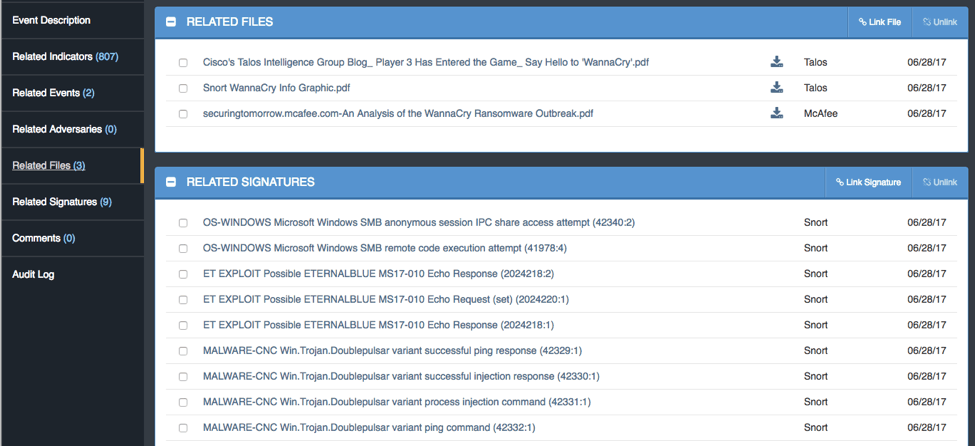

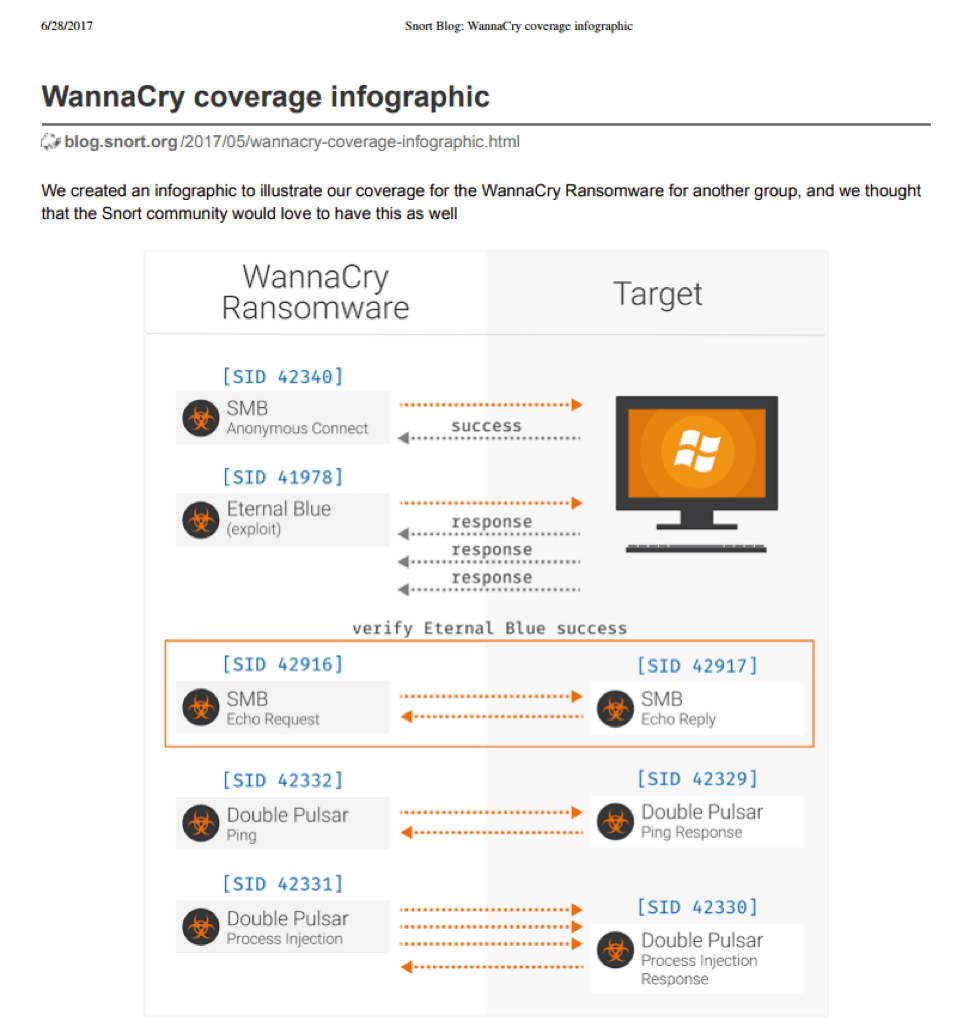

I can also publish collected Snort signatures and provide context embedded within the tool to help the SOC understand the flow of the detections.

Figure 10 – Related Signatures, Snort Rules in this case, from the Analyst created Adversary Profile for Wanna Cry (picture from ThreatQ version 3.1.1)

Figure 11: WannaCry Infographics, Source: Snort Blog

In short, we didn’t have to get bogged down searching through 29 million different posts. We used the existing feeds that we had already configured in the system, organized them via an internal event and then quickly applied additional information found from the web. We were able to identify what was missing for our protection plan, from Snort rules to using MD5s or SHAs to get additional hash-based indicators. We could even determine which integrations to use to not only get those protections in place but also in the right priority based on vulnerability data.

Of course the data will grow over time, but with the ThreatQ threat intelligence platform it all goes to the same collection and distribution point. You gain centralized control and distribution for a single source of truth for the protection of your network.

This is what sets ThreatQ apart from the rest of the field, and what we believe a threat intelligence platform is supposed to do.

0 Comments